I have spent the last six years obsessed with learning how to make patterns to sew my own dolls and soft toys, and I had spent the ten or so years prior to that learning how to make my own patterns for women’s clothing. The method I primarily use is called flat pattern drafting and it helps you make three dimensional, sculptural plush (like most of the stuffed animals that you might see in the stores). I will be offering trainings on this topic soon. However, I want to spend some time on some basic concepts that don’t really require this knowledge, and one of those is what I call 2D plush.

What are 2D plush (I started using this term a long time ago but recently realized some others do, as well, so I’m not sure who coined it)? Basically, this is how I refer to plush that are created by creating one, flat shape, sewing two pieces of fabric together in that shape, (usually) turning it and then stuffing it. Of course, once stuffed, it isn’t truly two-dimensional anymore, but three-dimensional! But it doesn’t rely on the pattern to create any of that dimension. And, it’s not nearly as 3d or shapely as a more complicated pattern.

I’ll admit, I didn’t really enjoy 2D plush when handmade plush first started getting more popular. I didn’t like how flat they looked and I also have a habit of wanting things to be as complicated as possible for no good reason–while these seemed simple. I still don’t often make fully 2D plush, but I often use a combination of 2D and 3D flat pattern drafting with my dolls and soft toys. And I have really come around to some of their merits.

If you stick around long enough to learn 3D flat pattern drafting from me, you’ll see it can be a lot of work. There are some situations where 2D is truly the better choice, so why make it harder than it needs to be!

Here are some advantages of 2D:

- 2D plush is really good to use with fabrics that are fluffy and really difficult to work with. Cutting these fabrics (think Luxe Cuddle) is often agonizing, what with the shedding and slipping around. So a very simple pattern reduces cutting time. In fact, one of the biggest advantages of a 2D pattern is that you can simply trace the shape (without seam allowance) onto the backside of the folded fabric, pin it, and sew on the line. You do still have to cut it out, but in this case you don’t need to worry as much about the fabric pieces staying together properly and slipping around.

- On a similar note, a 2D pattern often allows these fun and fluffy, yet FUSSY, fabrics to shine. Seamlines from a more complicated pattern will often be obscured by the longer fibers anyway, so why create extra work for yourself? The owl above is a 2D pattern with lots of dimension thanks to the fabric.

- 2D plush are great for stretchy fabrics. Many Waldorf dollmakers use a full body 2D doll pattern that has no darts at all. The fabric is so stretchy and stuffed so firmly that the doll will look round and full, and they use other techniques to add details like elbows and such. Making a more detailed pattern is actually counter productive if you’re using fabric with true stretch.

- 2D plush are great if you want to weight the plush heavily. This is a similar situation as above in that the extra amount of weight is going to sink down which means that any dimension you create with your seams will not be upheld the way it would with stuffing. The bat and owl shown above are heavily weighted.

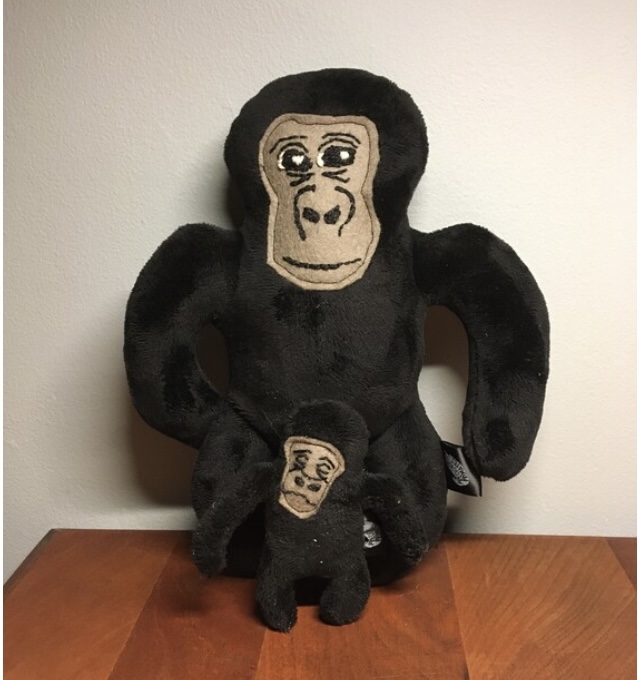

- 2D plush is a great choice when you’re making something tiny. The itsy-bitsy ape babies shown below are less than 5″ long. At that scale, you don’t want to be fussing with darts and seams.

- Finally, 2D plush is great if you want to use embroidery, appliqué or other embellishments as the primary feature of your plush. I like usually like to communicate expression and facial and body shape through the patterning itself (3D) but sometimes it’s fun to use the fabric almost as a canvas where you embroider, appliqué fabric pieces or even paint on it. In this case you want a flat surface without extra seams so that you can easily use these techniques, perhaps even in an embroidery hoop, so 2D is perfect. All of the 2D plush pictured in this post have tons of embroidered expression (that is, if you can pardon the poor photo quality).

So there you have it: 2D plush has a lot of room for possibility while keeping the pattern-making and machine sewing aspect nice and simple. It also means that you can dive right in as a plush-maker newbie and familiarize yourself with the fundamentals of fabric choice, sewing, and basic patterning. What questions do you have?