Edit, 10/25/19: Since publishing this post, I have been more exposed to actual autistic accounts and, in re-reading this, am aware of my ableist/allistic tone in terms of my assumptions about play needing to be a means to an end (neurotypical-like socializing) and the assumption that the play relates back to meaning-making of social interactions. That is, my daughter and other autistic kids can and will use toys however they wish and we can’t try to understand their play from within a neurotypical framework.

I love soft toys and dolls, so I really looked forward to being able to buy a lot of them for my daughter, and joining her in playing with them. Leading up to my daughter receiving her autism diagnosis, when she was around two, we noticed that she wasn’t really doing pretend play. Since then, she actually has started to do more pretend play with dolls and exhibits some nurturing behaviors with her stuffed animals. She often recites conversations she’s heard during the day with her toys (this is echolalia). She has also been handing us the monkey puppet and saying, “my turn with the monkey” which translates to, “I want you to use the monkey” [to interact with whatever toy she’s holding].

Although she still doesn’t engage with baby dolls or soft toys exactly the same way other kids her age might, I believe that they play an important role for her. In fact, I think they may even be more important to her social development than they would be to a neurotypical kid; they provide a safe and neutral way for her to make sense of the communication she’s trying to figure out in her every day life. She needs this extra “practice” with reciprocity and interaction. I, of course, am always ready to join her and have tried to see it the way she does rather than through my old ideas about play.

I recently found myself thinking about soft toys and neurodiverse children. For my daughter, as mentioned above, they have emerging importance and usefulness in practicing or rehearsing communication exchanges. I also think they have sensory value. I think she finds it reassuring to carry around different toys, especially if they can be easily held with one hand. I also think she enjoys the soft feel, but she doesn’t seem partial to certain types of fabric. I do notice that she seems to enjoy those with limbs that are easy to fling around.

What would a soft toy designer want to keep in mind if designing for autistic children or adults? I have tried researching the topic and surprisingly little has come up. One mother found an Ask Amy doll for her daughter which, while pretty standard in appearance, is an interactive doll and helped her daughter learn a lot of new skills. This, of course, is not a soft toy at all. The appearance and feel of the doll took a back seat to its technological offerings. There’s Lulladoll which isn’t that interesting in terms of design, but it mimics a heart beat and can be soothing for many children. This Lottie Doll comes with glasses and headphones to help with overwhelming sensory stimuli. The inspiration for this doll was “a little boy with a passion for all things space-related, who just happens to be autistic.” And there is the soft doll version of the Sesame Street character Julia who is autistic. In this case, the connection to autism is really just limited to the character and autism doesn’t appear to have been a consideration in the design (read this review –I concur with the author’s opinion).

Otherwise, when you search for autism doll, you often get an American Girl-looking doll with clothing that’s made of puzzle piece fabric. If you haven’t already picked up on this, the presence of autism in the doll making and soft toy world seems limited to: 1) a very literal representation of (one) autistic child, 2) a toy that has high sensory value–almost like a baby toy– which sort of takes away from its identity as a doll, 3) something that’s almost like a robot, or 4) a doll covered in puzzle piece fabric. As expected, companies seem interested in claiming that they have something to offer autistic kids, but the results are disappointing to me. The Lottie Doll seems successful, but only for kids who happen to identify with the one individual it was inspired by.

The Lottie Doll example leads us to the crux of the issue: if autism is a spectrum–nay, a three-dimensional color wheel–where each child has a unique constellation of preferences and characteristics, can you design “for” them? Even more so than other disabilities, autism is difficult to identify by particular features or characteristics that can translate to certain accessories or looks (e.g. deaf children with a hearing aid or cochlear implant). Besides, even with a disability that is associated with specific physical features, it isn’t necessarily that simple. There was a really interesting conversation in one of the doll making groups that I’m part of regarding the making of a cloth baby doll with Down Syndrome. One dollmaker said that she focused on customizing the dolls to have accessories or features that the children (recipients) themselves felt made them different–for example, thick glasses, surgery scars. She did not focus on giving them shorter necks or different eye shapes. She pointed out that those features are what others think of as being noticeable about the child with Down Syndrome, but not necessarily what feels representative to the child. She also mentioned changing certain things about the construction of the doll and their clothing to make them easier to handle for the children but also with different opportunities to develop motor skills (e.g. large buttons rather than Velcro). This really comes down to a bigger discussion about representation and inclusivity. This is where the independent, handmade market really can meet the needs of (at least some) children in a way that the commercial industry cannot.

As for the sensory features, sizing, fabric choices and other functions of the doll, I wonder if that’s also too dependent on the individual’s preference or if there are general features that would be appealing to most autistic children and adults? Some might love a really soft and silky feeling material like minky, while for others that may be overwhelming. Some might like a heavily weighted doll. Some might like a bright, colorful, detailed face and others might like something more minimalist. Personally, I have my own extremely specific preferences when it comes to the design, expression, proportions and fabric choice of soft dolls and toys, which is why I started making them myself.

When considering designing for the neuro-diverse, taken-for-granted perspectives on play are up for debate. For example, Waldorf/Steiner-style dollmaking is all about a simple, almost blank face because they believe this encourages the child to come up with their own ideas about how the doll feels and to develop empathy and imagination. But, if the child already struggles with reading facial expressions and with pretend play, does this still hold true? Is a highly expressive, cartoony commercial doll actually better than a simple doll? The answer is likely not straightforward, but it’s an interesting question to consider.

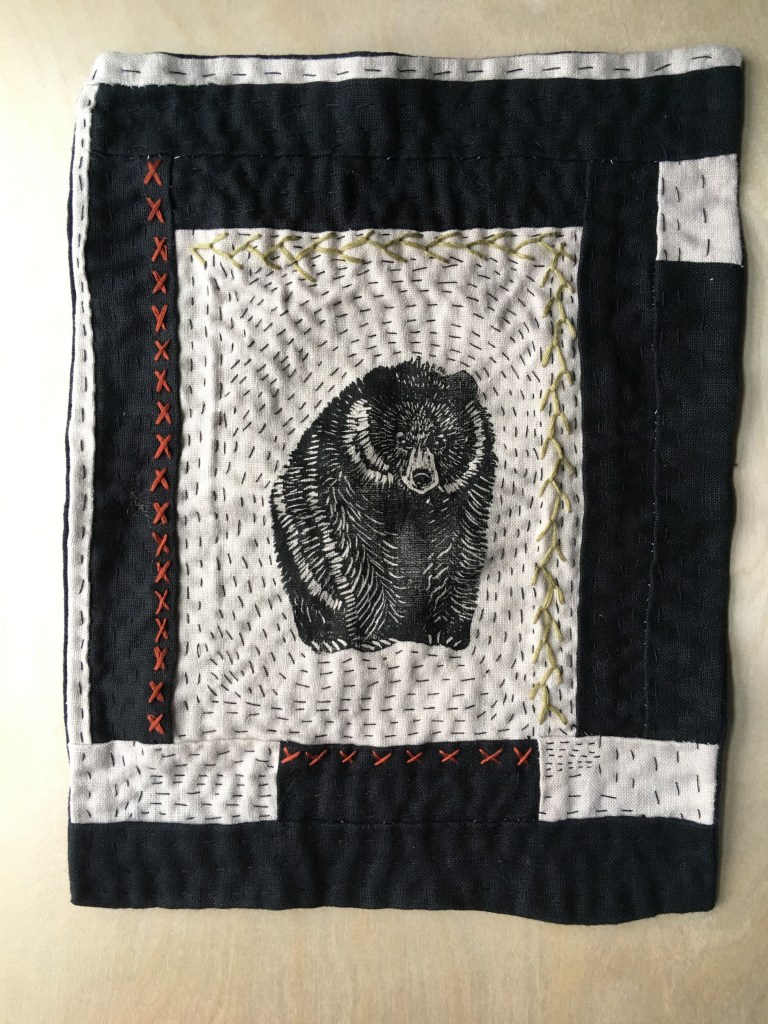

Perhaps I’ve already made it too complicated. This article is about a young adult with autism who carries his stuffed bear everywhere as a comfort object. In this case, the value of the bear probably has little to do with its design. It’s just a simple, classic plush friend: easy to form an attachment do, inherently comforting and with great power to help cope with daily stressors, simply because it is a soft toy.